| F.J. Ossang: The Grand Insurrectionary Style

Nicole Brenez |

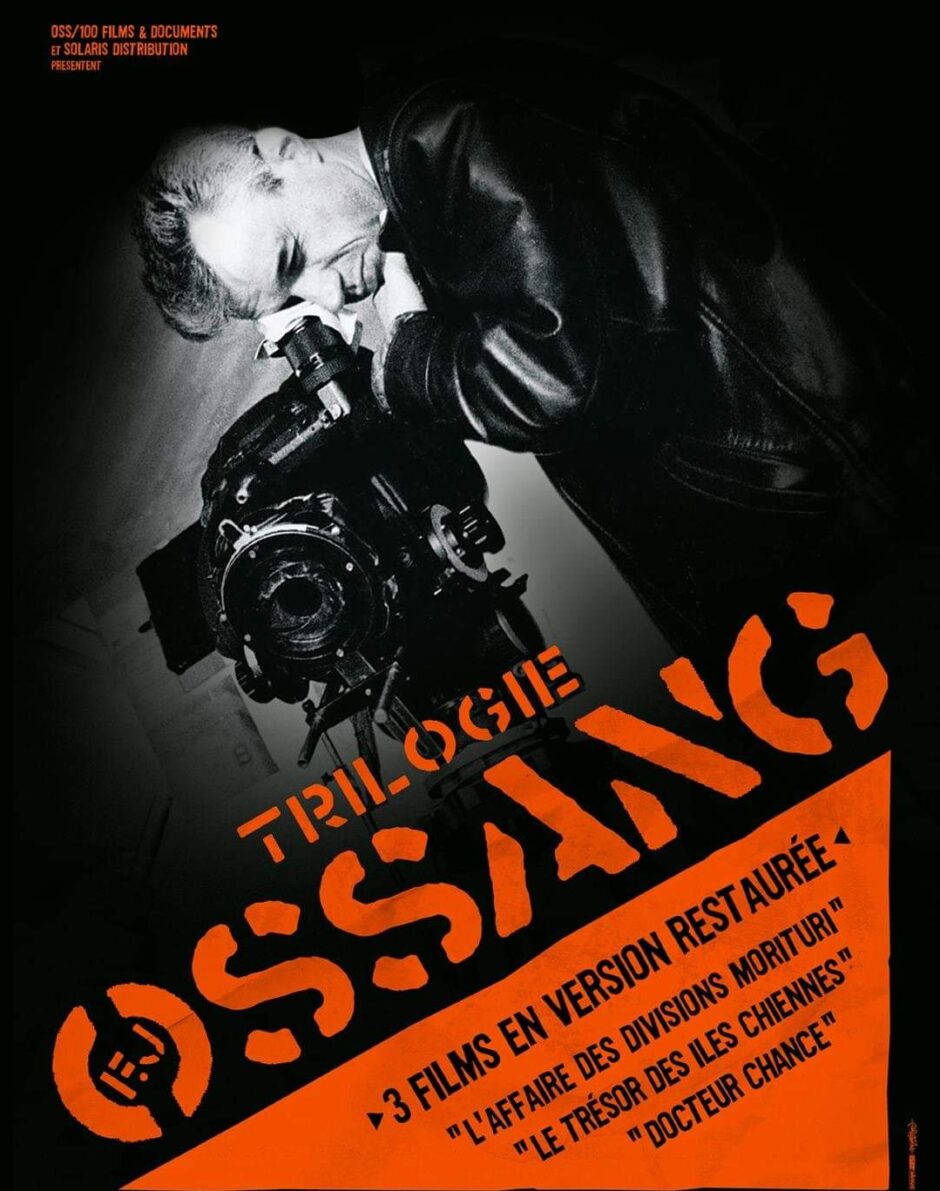

| Cinematographer, writer, singer, messenger: F.J. Ossang, born in the Cantal on 7 August 1956. Practices poetry in all its forms. Subject of a retrospective at International Film Festival Rotterdam, 25 January – 5 February 2011.

He makes music – nine albums with his band MKB (Messageros Killer Boys) Fraction Provisoire; he writes prose – some twenty books, including De la destruction pure (1977), Corpus d’octobre (1980), Descente aux tombeaux (1992), Unité 101 (2006) and the emblematic Génération néant (1993); he makes films – ten movies and as many visual poems, if poetry means a violent outburst of vitality.

Ossang pretends not to concern himself with painting and drawing, but he has created sublimely beautiful tones of grey in Silencio (2007), and always gives carte blanche to his outstanding cameramen: Darius Khondji for Le trésor des îles chiennes (1990), Remi Chevrin for Docteur Chance (1997) and Gleb Teleshov for Dharma Guns (2011), making it possible for them to create radiant images without equal on any silver screen in the world. Joe Strummer said (after Docteur Chance) that Ossang is the only filmmaker he would immediately work with again. Ossang’s work belongs to the grand insurrectionary style that runs throughout the history of anti-art, from Richard Huelsenbeck to the films of Holger Meins. (1) Ossang’s aesthetic has the singular capacity of displaying his expressive, narrative and rhythmic inventions in the context of an iconography of the most popular kind – in such a way that their poetic intensity transforms archetypes (bad guys, social groups, femmes fatales, warriors) back into prototypes, and facile effigies into fascinating creatures distraught with love, emotions, flux and space. He is a great filmmaker of adventure: bold images and scenarios in the form of expressive epic poems; the psychological vicissitudes of characters who move from rapture to ecstasy until they evaporate in the upper atmosphere because they can never again descend – like, for instance, at the end of Docteur Chance. The story does not present events in the dreary manner of the average film, but allows room for visual developments, like Jean Epstein or the Soviet masters, including the Mikhail Kalatozov of I Am Cuba (1964). Instead of showing the chase or the race, Ossang films the world that produces such velocity, plunging into the substance of colours and the experience of sensations. Whatever the story may be, it springs from a love of words: not so much the dialogue but the formulation, the insert, the slogan, the point – giving rise to the monumental handwriting that so characterises his work. |

(1) Other publications by Ossang: Le Berlinterne (1976), Revue CEE (1977-79), Alcôve clinique (1981), L’Ode à Pronto Rushtonsky (1994), Au bord de l’aurore (1994), les 59 jours (1999), Landscape et silence (2000), Tasman Orient (2001), Ténèbre sur les planètes (2006), WS Burroughs/Formule mort (2007). Most influential MKB Fraction Provisoire albums: Terminal Toxique (1982), L’affaire des divisions Morituri (1984), Hôtel du Labrador (1988), Le Trésor des îles chiennes (soundtrack, 1991), Docteur Chance 93 (1993), Feu! (1994), Frenchies Bad Indians White Trash (1994), MKB – Live (1996), Docteur Chance (soundtrack, 1998), Baader Meinhof Wagen! (2006). For extracts from many of these works, see here.

|

| But, most of all, Ossang’s cinema involves bringing back epic gestures to popular visual culture, tearing things apart until they become inconceivably beautiful. In Dharma Guns (2010), he creates a poetry of the ‘final images’, fits of giddiness, psychological account-settling that invade our brains as death approaches – the gleams and flashes he has still to extract from his much-loved argentic.

This gargantuan appetite for cinema also comes to the fore in his first published texts. Issue number 7 of CEE, which was published by Christian Bourgois in 1979 and whose contributors included W.S. Burroughs, Pierre Molinier, André Masson, Bernard Noël, Christian Prigent, Claude Pélieu, and a key figure in Ossang’s universe, poet Stanislas Rodanski (a meteor from the twilight days of surrealism), contains the text ‘Video Scripts and Tribal Song’, a wild mix of manifesto, diary, screenplay, meditation and pamphlet which, in retrospect, reveals itself as an aesthetic platform for his films yet to be made.

In this text we can read, with the manoeuvres of a global civil war as background music and punctuated frames as visual montage, like so many frames and future film inserts (including one borrowed from Raoul Haussmann): |

| Moreover, there has never been art, only an incessant war of abuses against social time, in favour of the diversity of the real. There are only – and especially – actions to liberate what is always open! |

| Following the example of his riotous prose, Ossang’s romantic, apocalyptic punk films are part of a guerrilla ethos in which everything serves as a weapon: an exclamation mark, a capital letter, an iris, a fade out, a homage to Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), the description of an unconditional love. So many salvos in the thick, electronic fog that makes up the world. For Ossang, everything is a struggle: the raging energy of an endless and futile battle against the order of things. As soon as he embarks on directing La dernière énigme (1982), loosely based on Gianfranco Sanguinetti’s Situationist treatise On Terrorism and the State which had just been published in French, Ossang combines the strength of constructivism (poetry of the factory), Gil Wolman (a tribute to The Anticoncept) (2) and W.S. Burroughs (freedom of montage). A film has to be an attack: against common sense, against sadness, against all forms of control, such as allocation and identification. |

(2) For the text of Wolman’s 1952 film The Anticoncept, see here. |

| Dada Rock ‘n’ Roll Guerrillas. The driving force of the guerrilla is the absolute rejection of a demarcated battleground. For the mental guerrilla, it is absolute rejection of any fixed cultural register. (3) | (3) Ossang, ‘Video Scripts and Tribal Song’, CEE, no. 7 (1979). |

| Some great poets, such as Epstein or José Val del Omar, were of the opinion that cinema – an intelligent machine – had the power to reveal the harmonies according to which the world is structured. In contrast, a film by Ossang the musician lays claim to chaos, intoxication, pure and inescapable disorder. He does not manage anything, especially not the emotions of some drummed-up viewer; he does not tell a story, but only shows how we are at the mercy of history, bombarding us with sensations and splendour. He styles himself like a conspiracy in which, to survive, no one should understand anything; he invents a different language and codes akin to a secret society or unflinching prisoners preparing their escape; he creates an explosion in the course of the world, an illuminated opening through which one can perhaps escape or die – or probably both at once.

|

| Cinema is the last chance, it is unitarian and collective art. Cinema is the great critical force of other forms of expression, it reinterprets literature. I think that in the 20th Century cinema has disrupted literature, that the silent film was the upheaval of storytelling by means of a network that rises above a linear storyline. Specific to cinema is not travelling outside of time, but the creation of a kind of disruption between time and space that corresponds to the acceleration of time in society. We can jump forward and then back again, although memory only works relatively. Going back results in a loss of time, and in the end about the only thing left to remember is the light – to create a future. (4) |

(4) Ossang, La Gazette des scénaristes, no. 15 (Winter 2001). |

Lux Fecit F.J. Ossang, dark light of intelligence and love. His heroes are named Ezra Pound, Roger-Gilbert Lecomte, Josef von Sternberg, Orson Welles, Glauber Rocha and Georg Trakl. In passing, we also discover that, in his eyes, the French geniuses are Arthur Cravan, Jacques Vaché, Jacques Rigaut and Guy Debord. Yet it is Hegel, the great inventor of negation, who provides the formula for the vertiginous routes to the unbound embarked upon by Ossang’s characters, and for the passionate spirit that runs through this body of work: ‘Being free is nothing. Becoming free is everything’.

La dernière énigme (The Last Enigma, 1982) In-between essay and fiction, La dernière énigme established Ossang’s formal territory: a contemporary mythology. Inspired by the book On Terrorism and the State by Gianfranco Sanguinetti, it evokes visual echoes of political events, where a generation forfeits all revolutionary aspirations due to state terrorism. Shot using two cans of Kodak XX 16mm film.

La Zone: the poor, dangerous quarters of Paris (George Lacombe, 1928); the administrative zone where Orpheus looks for his lost Eurydice (Jean Cocteau, 1950); Interzone – the working title for William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (1959). In 1983, Ossang created a synthesis of all these territories of unrest under a banner of dead colours.

‘A story of gladiators against the background of the German question. The men sell their life rather than let themselves waste away in a territory controlled by the European middle class. One of them has become a star to the underworld, but eventually cracks up. There is but one way out: spill the beans to the press … ’ (Ossang).Played as a futuristic epic, L’affaire des divisions Morituri concerns the rebellion brewing amongst European youth after members of the Red Army Faction (most of whom were filmmakers) died in prison. The imagery harks back to the original revolt by Spartacus, but suddenly the black and white curtain is torn down and we are faced with the naked oppression of ‘sensory deprivation’ and State crimes. A mythical soundtrack consists of musical fragments from the most radical bands of the time: MKB Fraction Provisoire, Cabaret Voltaire, Tuxedomoon, Throbbing Grisle, Lucrate Milk. An emblem of French punk cinema.

The soundtrack to Le trésor des îles chiennes has memorable songs like ‘Pièces du sommeil’, ‘Descente sur la Cisteria ’, ‘Désastre des escorte’, ‘Passe des destitués’, ‘Le chant des hyènes’ and the original ‘Soleil trahi’. They accelerate the psychological journey of characters lost in hallucinations full of intrigue. Against contemporary consumerism are posed the expressive wealth, pugnacious energy and experimental sincerity of Ossang’s island inhabitants. Against a backdrop of ash and ancient lava, they flee for the darkness in their jeeps, and perpetuate the art of drug use: a legacy from centuries of black Romanticism. This is their real treasure, gathered by poets addicted to their craft. Their arsenal is not so much Kalashnikovs but ‘le prince cutter’ (as FJ will later sing in ‘Claude Pélieu was here’). That is to say, the strength to cut beyond the dotted lines, the instinct to avoid all deterrents to abandonment in intoxication. Before finding several rolls of colour film from the German army and realising twenty minutes of pure chromatic genius in Ivan the Terrible (1944), Sergei Eisenstein had dedicated some pages to colour in film. In a story about fugitive lovers, Docteur Chance, the first colour film by an expert in black-and-white cinema, issues from the same experimental excitement: how do you bring a film to the level of the chromatic initiatives in painting, as in certain medieval altarpieces, engravings by William Blake or paintings by Asger Jorn? In his Notes de travail (1996), Ossang elucidates: ‘This film should have the razor-sharp and vaguely coloured purity of a poem by Georg Trakl – no to a cinema more miserable than misery, more sexual than sex, heavier than the lead it paraphrases. Detail: a black-and-white close-up doesn’t have the same effect as a close-up in colour (why?). Why do the scripts of contemporary films seem “comatised” by emanations? Defilement of colour by structures. Deterritorialisation’. Silencio, Vladivostok and Ciel etient!: three silver pearls that together form the Trilogie du paysage or Landscape Trilogy. The visual poem Silencio follows in the tradition of documentary elegies that began with the films of Rudy Burckhardt and Charles Sheeler. But in the era of Throbbing Gristle, poetry must measure itself against industrial disasters, invisible nuclear apocalypses, a travel report, an optical meditation, an overwhelming array of black and white tones, a love song, a progression of dim phantoms in the terrifying caverns of hope … strike! ‘Between word and worlds, teeming with mysteries’, wrote the psychedelic poet Claude Pélieu about Ossang. The fragmentary Vladivostok cultivates the wealth of such in-between places. A concentration of Ossangian poetry, the outcome of his happy collaboration with director of photography Gleb Teleschov. Before this, Ossang films were not comparable to other films. But Ciel éteint! calls to mind early films by Philippe Garrel (Marie pour mémoire [1967], Le révélateur [1968]), closely related to anarchist filmmaker Jean-Pierre Lajournade. With the mythological everydayness of the young, destitute lovers Philémon and Baucis live in their cottage (made of reed in Ovid, made of wood in Ossang). At the end of the credits, we find the most beautiful visual declaration of love ever. The fable: a young man – poet, scriptwriter and warrior – dies. How do you reconstruct the images in his brain? What do we see in our moment of death? Can the spirit understand the causes of death and clear a path for itself to another life? In what kind of form do these these final images manifest? Will they dazzle? A feast of lights? An invasion? As memories, hypotheses, assumptions? The magisterial expressiveness of Dharma Guns allows us to experience the impulses of optical nerves and synapses. Ossang has grafted the film onto the central nervous system, the very place where mental images are born. ‘My eyes have drunk’, we hear in this worthy treatment of Antonin Artaud’s expectations of cinema. Dharma Guns is constantly airborne, buzzing, pushing its way towards the isle of the dead. A masterpiece that slowly moves before our eyes, in the staggering slow motion of certainty, into the company of Nosferatu (1922) and Vampyr (1932). |

© Nicole Brenez February 2011.

Commissioned and translated from the French by International Film Festival Rotterdam, revised by the author and LOLA.

Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors.